Revised Kyoto Convention

Revised Kyoto Convention

Contracting Parties

Global list

Global list

POSITION AS REGARDS RATIFICATIONS AND ACCESSIONS

(as of 25 June 2010)

International Convention on the simplification and harmonization of Customs procedures (as amended)

(Revised Kyoto Convention)

(done at Kyoto on 18 May 1973, amended on 26 June 1999 and entered into force on 3 February 2006.)

|

CONTRACTING |

Dates of signature |

Dates of signature |

|

ALGERIA |

- |

26-06-1999 |

|

AUSTRALIA |

18-04-2000 |

10-10-2000 |

|

AUSTRIA |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

AZERBAIJAN |

- |

03-02-2006 |

|

BELGIUM |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

BOTSWANA |

- |

26-06-2006 |

|

BULGARIA |

- |

17-03-2004 |

|

CANADA |

- |

09-11-2000 |

|

CHINA |

- |

15-06-2000 |

|

CONGO (Dem. Rep. of the) |

15-06-2000 |

- |

|

CROATIA |

- |

02-11-2005 |

|

CUBA |

- |

24-06-2009 |

|

CYPRUS |

- |

25-10-2004 |

|

CZECH REPUBLIC |

30-06-2000 |

17-09-2001 |

|

DENMARK |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

EGYPT |

- |

08-01-2008 |

|

ESTONIA |

- |

28-07-2006 |

|

EUROPEAN UNION |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

FINLAND |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

FIJI |

- |

26-01-2010 |

|

FRANCE |

- |

22-07-2004 |

|

GERMANY |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

GREECE |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

HUNGARY |

- |

29-04-2004 |

|

INDIA |

- |

03-11-2005 |

|

IRELAND |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

ITALY |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

JAPAN |

- |

26-06-2001 |

|

JORDAN |

- |

08-12-2006 |

|

KAZAKHSTAN |

- |

19-06-2009 |

|

KENYA |

- |

25-06-2010 |

|

KOREA |

- |

19-02-2003 |

|

LATVIA |

15-06-2000 |

20-09-2001 |

|

LESOTHO |

- |

15-06-2000 |

|

LITHUANIA |

- |

27-04-2004 |

|

LUXEMBOURG |

- |

26-01-2006 |

|

MADAGASCAR |

- |

27-06-2007 |

|

MALAYSIA |

- |

30-06-2008 |

|

MALI |

- |

04-05-2010 |

|

MALTA |

- |

11-05-2010 |

|

MAURITIUS |

- |

24-09-2008 |

|

MONGOLIA |

- |

01-07-2006 |

|

MONTENEGRO |

- |

23-06-2008 |

|

MOROCCO |

- |

16-06-2000 |

|

NAMIBIA |

- |

03-02-2006 |

|

NETHERLANDS |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

NEW ZEALAND |

- |

07-07-2000 |

|

NORWAY |

- |

09-01-2007 |

|

PAKISTAN |

- |

01-10-2004 |

|

PHILIPPINES |

- |

25-06-2010 |

|

POLAND |

- |

09-07-2004 |

|

PORTUGAL |

- |

15-04-2005 |

|

QATAR |

- |

13-07-2009 |

|

SENEGAL |

- |

21-03-2006 |

|

SERBIA |

- |

18-09-2007 |

|

SLOVAKIA |

15-06-2000 |

19-09-2002 |

|

SLOVENIA |

- |

27-04-2004 |

|

SOUTH AFRICA |

- |

18-05-2004 |

|

SPAIN |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

SRI LANKA |

26-06-1999 |

26-06-2009 |

|

SUDAN |

- |

16-08-2009 |

|

SWEDEN |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

SWITZERLAND |

29-06-2000 |

26-06-2004 |

|

THE FORMER YUGOSLAV REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA |

- |

28-07-2009 |

|

TURKEY |

- |

03-05-2006 |

|

UGANDA |

- |

27-06-2002 |

|

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES |

- |

31/05/2010 |

|

UNITED KINGDOM |

- |

30-04-2004 |

|

UNITED STATES |

- |

06-12-2005 |

|

VIETNAM |

- |

08-01-2008 |

|

ZAMBIA |

26-06-1999 |

01-07-2006 |

|

ZIMBABWE |

26-06-1999 |

10-02-2003 |

Number of Contracting Parties: 71

Listed by region

Listed by region

CONTRACTING PARTIES TO THE REVISED KYOTO CONVENTION

BY WCO REGION

EAST AND SOUTHERN AFRICA

- Botswana

- Kenya

- Lesotho

- Madagascar

- Mauritius

- Namibia

- South Africa

- Uganda

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

10 out of 22 Members

EUROPE

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia

- European Union

- Finland

- Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Ireland

- Italy

- Kazakhstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Montenegro

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Poland

- Portugal

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

36 out of 51 Members + European Union

FAR EAST, SOUTH AND SOUTH EAST ASIA, AUSTRALASIA AND THE PACIFIC ISLANDS

- Australia

- China

- Fiji

- India

- Japan

- Korea

- Malaysia

- Mongolia

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Sri Lanka

- Vietnam

13 out of 33 Members

NORTH OF AFRICA, NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST

- Algeria

- Egypt

- Jordan

- Morocco

- Qatar

- Sudan

- United Arab Emirates

7 out of 17 Members

SOUTH AMERICA, NORTH AMERICA, CENTRAL AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN

- Canada

- Cuba

- United States

3 out of 31 Members

WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA

- Mali

- Senegal

2 out of 22 Members

Listed in graphical form

Instruments and Notifications

Body of the Convention

Preamble

PREAMBLE

The Contracting Parties to the present Convention established under the auspices of the Customs Co-operation Council,

ENDEAVOURING to eliminate divergence between the Customs procedures and practices of Contracting Parties that can hamper international trade and other international exchanges,

DESIRING to contribute effectively to the development of such trade and exchanges by simplifying and harmonizing Customs procedures and practices and by fostering international co-operation,

NOTING that the significant benefits of facilitation of international trade may be achieved without compromising appropriate standards of Customs control,

RECOGNIZING that such simplification and harmonization can be accomplished by applying, in particular, the following principles:

- the implementation of programmes aimed at continuously modernizing Customs procedures and practices and thus enhancing efficiency and effectiveness,

- the application of Customs procedures and practices in a predictable, consistent and transparent manner,

- the provision to interested parties of all the necessary information regarding Customs laws, regulations, administrative guidelines, procedures and practices,

- the adoption of modern techniques such as risk management and audit-based controls, and the maximum practicable use of information technology,

- co-operation wherever appropriate with other national authorities, other Customs administrations and the trading communities,

- the implementation of relevant international standards,

- the provision to affected parties of easily accessible processes of administrative and judicial review,

CONVINCED that an international instrument incorporating the above objectives and principles that Contracting Parties undertake to apply would lead to the high degree of simplification and harmonization of Customs procedures and practices which is an essential aim of the Customs Co-operation Council, and so make a major contribution to facilitation of international trade,

Have agreed as follows:

Chapter I - Definitions

CHAPTER I

Article 1

Definitions

For the purposes of this Convention:

A. "Standard " means a provision the implementation of which is recognized as necessary for the achievement of harmonization and simplification of Customs procedures and practices;

B. "Transitional Standard " means a Standard in the General Annex for which a longer period for implementation is permitted;

C. "Recommended Practice " means a provision in a Specific Annex which is recognized as constituting progress towards the harmonization and the simplification of Customs procedures and practices, the widest possible application of which is considered to be desirable;

D. "National legislation " means laws, regulations and other measures imposed by a competent authority of a Contracting Party and applicable throughout the territory of the Contracting Party concerned, or treaties in force by which that Party is bound;

E. "General Annex " means the set of provisions applicable to all the Customs procedures and practices referred to in this Convention;

F. "Specific Annex " means a set of provisions applicable to one or more Customs procedures and practices referred to in this Convention;

G. "Guidelines " means a set of explanations of the provisions of the General Annex, Specific Annexes and Chapters therein which indicate some of the possible courses of action to be followed in applying the Standards, Transitional Standards and Recommended Practices, and in particular describing best practices and recommending examples of greater facilities;

H. "Permanent Technical Committee " means the Permanent Technical Committee of the Council;

I. "Council " means the Organization set up by the Convention establishing a Customs Co-operation Council, done at Brussels on 15 December 1950;

J. "Customs or Economic Union " means a Union constituted by, and composed of, States which has competence to adopt its own regulations that are binding on those States in respect of matters governed by this Convention, and has competence to decide, in accordance with its internal procedures, to sign, ratify or accede to this Convention.

Chapter II - Scope and Structure

CHAPTER II

SCOPE AND STRUCTURE

Article 2

Scope of the Convention

Each Contracting Party undertakes to promote the simplification and harmonization of Customs procedures and, to that end, to conform, in accordance with the provisions of this Convention, to the Standards, Transitional Standards and Recommended Practices in the Annexes to this Convention. However, nothing shall prevent a Contracting Party from granting facilities greater than those provided for therein, and each Contracting Party is recommended to grant such greater facilities as extensively as possible.

Article 3

The provisions of this Convention shall not preclude the application of national legislation with regard to either prohibitions or restrictions on goods which are subject to Customs control.

Article 4

Structure of the Convention

1. The Convention comprises a Body, a General Annex and Specific Annexes.

2. The General Annex and each Specific Annex to this Convention consist, in principle, of Chapters which subdivide an Annex and comprise:

A.definitions; and

B. Standards, some of which in the General Annex are Transitional Standards.

3. Each Specific Annex also contains Recommended Practices.

4. Each Annex is accompanied by Guidelines, the texts of which are not binding upon Contracting Parties.

Article 5

For the purposes of this Convention, any Specific Annex(es) or Chapter(s) therein to which a Contracting Party is bound shall be construed to be an integral part of the Convention, and in relation to that Contracting Party any reference to the Convention shall be deemed to include a reference to such Annex(es) or Chapter(s).

Chapter III - Management of the Convention

CHAPTER III

MANAGEMENT OF THE CONVENTION

Article 6

Management Committee

1. There shall be established a Management Committee to consider the implementation of this Convention, any measures to secure uniformity in the interpretation and application thereof, and any amendments proposed thereto.

2. The Contracting Parties shall be members of the Management Committee.

3. The competent administration of any entity qualified to become a Contracting Party to this Convention under the provisions of Article 8 or of any Member of the World Trade Organization shall be entitled to attend the sessions of the Management Committee as an observer. The status and rights of such Observers shall be determined by a Council Decision. The aforementioned rights cannot be exercised before the entry into force of the Decision.

4. The Management Committee may invite the representatives of international governmental and non-governmental organizations to attend the sessions of the Management Committee as observers.

5. The Management Committee:

A. shall recommend to the Contracting Parties:

I. amendments to the Body of this Convention;

II. amendments to the General Annex, the Specific Annexes and Chapters therein and the incorporation of new Chapters to the General Annex;

III. the incorporation of new Specific Annexes and new Chapters to Specific Annexes;

B. may decide to amend Recommended Practices or to incorporate new Recommended Practices to Specific Annexes or Chapters therein in accordance with Article 16;

C. shall consider implementation of the provisions of this Convention in accordance with Article 13, paragraph 4;

D. shall review and update the Guidelines;

E. shall consider any other issues of relevance to this Convention that may be referred to it;

F. shall inform the Permanent Technical Committee and the Council of its decisions.

6. The competent administrations of the Contracting Parties shall communicate to the Secretary General of the Council proposals under paragraph 5 (a), (b), (c) or (d) of this Article and the reasons therefor, together with any requests for the inclusion of items on the Agenda of the sessions of the Management Committee. The Secretary General of the Council shall bring proposals to the attention of the competent administrations of the Contracting Parties and of the observers referred to in paragraphs 2, 3 and 4 of this Article.

7. The Management Committee shall meet at least once each year. It shall annually elect a Chairman and Vice-Chairman. The Secretary General of the Council shall circulate the invitation and the draft Agenda to the competent administrations of the Contracting Parties and to the observers referred to in paragraphs 2, 3 and 4 of this Article at least six weeks before the Management Committee meets.

8. Where a decision cannot be arrived at by consensus, matters before the Management Committee shall be decided by voting of the Contracting Parties present. Proposals under paragraph 5 (a), (b) or (c) of this Article shall be approved by a two-thirds majority of the votes cast. All other matters shall be decided by the Management Committee by a majority of the votes cast.

9. Where Article 8, paragraph 5 of this Convention applies, the Customs or Economic Unions which are Contracting Parties shall have, in case of voting, only a number of votes equal to the total votes allotted to their Members which are Contracting Parties.

10. Before the closure of its session, the Management Committee shall adopt a report. This report shall be transmitted to the Council and to the Contracting Parties and observers mentioned in paragraphs 2, 3 and 4.

11. In the absence of relevant provisions in this Article, the Rules of Procedure of the Council shall be applicable, unless the Management Committee decides otherwise.

Article 7

For the purpose of voting in the Management Committee, there shall be separate voting on each Specific Annex and each Chapter of a Specific Annex.

A. Each Contracting Party shall be entitled to vote on matters relating to the interpretation, application or amendment of the Body and General Annex of the Convention.

B. As regards matters concerning a Specific Annex or Chapter of a Specific Annex that is already in force, only those Contracting Parties that have accepted that Specific Annex or Chapter therein shall have the right to vote.

C. Each Contracting Party shall be entitled to vote on drafts of new Specific Annexes or new Chapters of a Specific Annex.

Chapter IV - Contracting Party

CHAPTER IV

CONTRACTING PARTY

Article 8

Ratification of the Convention

1. Any Member of the Council and any Member of the United Nations or its specialized agencies may become a Contracting Party to this Convention:by signing it without reservation of ratification;

A. by signing it without reservation of ratification;

B. by depositing an instrument of ratification after signing it subject to ratification; or

C. by acceding to it.

2. This Convention shall be open until 30th June 1974 for signature at the Headquarters of the Council in Brussels by the Members referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article. Thereafter, it shall be open for accession by such Members.

3. Any Contracting Party shall, at the time of signing, ratifying or acceding to this Convention, specify which if any of the Specific Annexes or Chapters therein it accepts. It may subsequently notify the depositary that it accepts one or more Specific Annexes or Chapters therein.

4. Contracting Parties accepting any new Specific Annex or any new Chapter of a Specific Annex shall notify the depositary in accordance with paragraph 3 of this Article.

5. (a) Any Customs or Economic Union may become, in accordance with paragraphs 1, 2 and 3 of this Article, a Contracting Party to this Convention. Such Customs or Economic Union shall inform the depositary of its competence with respect to the matters governed by this Convention. Such Customs or Economic Union shall also inform the depositary of any substantial modification in the extent of its competence.

(b) A Customs or Economic Union which is a Contracting Party to this Convention shall, for the matters within its competence, exercise in its own name the rights, and fulfil the responsibilities, which the Convention confers on the Members of such a Union which are Contracting Parties to this Convention. In such a case, the Members of such a Union shall not be entitled to individually exercise these rights, including the right to vote.

Article 9

1. Any Contracting Party which ratifies this Convention or accedes thereto shall be bound by any amendments to this Convention, including the General Annex, which have entered into force at the date of deposit of its instrument of ratification or accession.

2. Any Contracting Party which accepts a Specific Annex or Chapter therein shall be bound by any amendments to the Standards contained in that Specific Annex or Chapter which have entered into force at the date on which it notifies its acceptance to the depositary. Any Contracting Party which accepts a Specific Annex or Chapter therein shall be bound by any amendments to the Recommended Practices contained therein, which have entered into force at the date on which it notifies its acceptance to the depositary, unless it enters reservations against one or more of those Recommended Practices in accordance with Article 12 of this Convention.

Article 10

Application of the Convention

1. Any Contracting Party may, at the time of signing this Convention without reservation of ratification or of depositing its instrument of ratification or accession, or at any time thereafter, declare by notification given to the depositary that this Convention shall extend to all or any of the territories for whose international relations it is responsible. Such notification shall take effect three months after the date of the receipt thereof by the depositary. However, this Convention shall not apply to the territories named in the notification before this Convention has entered into force for the Contracting Party concerned

2. Any Contracting Party which has made a notification under paragraph 1 of this Article extending this Convention to any territory for whose international relations it is responsible may notify the depositary, under the procedure of Article 19 of this Convention, that the territory in question will no longer apply this Convention.

Article 11

For the application of this Convention, a Customs or Economic Union that is a Contracting Party shall notify to the Secretary General of the Council the territories which form the Customs or Economic Union, and these territories are to be taken as a single territory.

Acceptance of the provisions and reservations

Article 12

Acceptance of the provisions and reservations

1. All Contracting Parties are hereby bound by the General Annex.

2. A Contracting Party may accept one or more of the Specific Annexes or one or more of the Chapters therein. A Contracting Party which accepts a Specific Annex or Chapter(s) therein shall be bound by all the Standards therein. A Contracting Party which accepts a Specific Annex or Chapter(s) therein shall be bound by all the Recommended Practices therein unless, at the time of acceptance or at any time thereafter, it notifies the depositary of the Recommended Practice(s) in respect of which it enters reservations, stating the differences existing between the provisions of its national legislation and those of the Recommended Practice(s) concerned. Any Contracting Party which has entered reservations may withdraw them, in whole or in part, at any time by notification to the depositary specifying the date on which such withdrawal takes effect.

3. Each Contracting Party bound by a Specific Annex or Chapter(s) therein shall examine the possibility of withdrawing any reservations to the Recommended Practices entered under the terms of paragraph 2 and notify the Secretary General of the Council of the results of that review at the end of every three-year period commencing from the date of the entry into force of this Convention for that Contracting Party, specifying the provisions of its national legislation which, in its opinion, are contrary to the withdrawal of the reservations.

Article 13

Implementation of the provisions

1. Each Contracting Party shall implement the Standards in the General Annex and in the Specific Annex(es) or Chapter(s) therein that it has accepted within 36 months after such Annex(es) or Chapter(s) have entered into force for that Contracting Party.

2. Each Contracting Party shall implement the Transitional Standards in the General Annex within 60 months of the date that the General Annex has entered into force for that Contracting Party.

3. Each Contracting Party shall implement the Recommended Practices in the Specific Annex(es) or Chapter(s) therein that it has accepted within 36 months after such Specific Annex(es) or Chapter(s) have entered into force for that Contracting Party, unless reservations have been entered as to one or more of those Recommended Practices.

4. (a) Where the periods provided for in paragraph 1 or 2 of this Article would, in practice, be insufficient for any Contracting Party to implement the provisions of the General Annex, that Contracting Party may request the Management Committee, before the end of the period referred to in paragraph 1 or 2 of this Article, to provide an extension of that period. In making the request, the Contracting Party shall state the provision(s) of the General Annex with regard to which an extension of the period is required and the reasons for such request.

(b) In exceptional circumstances, the Management Committee may decide to grant such an extension. Any decision by the Management Committee granting such an extension shall state the exceptional circumstances justifying the decision and the extension shall in no case be more than one year. At the expiry of the period of extension, the Contracting Party shall notify the depositary of the implementation of the provisions with regard to which the extension was granted.

Article 14

Settlement of disputes

1. Any dispute between two or more Contracting Parties concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention shall so far as possible be settled by negotiation between them.

2. Any dispute which is not settled by negotiation shall be referred by the Contracting Parties in dispute to the Management Committee which shall thereupon consider the dispute and make recommendations for its settlement.

3. The Contracting Parties in dispute may agree in advance to accept the recommendations of the Management Committee as binding.

Article 15

Amendments to the Convention

1. The text of any amendment recommended to the Contracting Parties by the Management Committee in accordance with Article 6, paragraph 5 (a) (i) and (ii) shall be communicated by the Secretary General of the Council to all Contracting Parties and to those Members of the Council that are not Contracting Parties.

2. Amendments to the Body of the Convention shall enter into force for all Contracting Parties twelve months after deposit of the instruments of acceptance by those Contracting Parties present at the session of the Management Committee during which the amendments were recommended, provided that no objection is lodged by any of the Contracting Parties within a period of twelve months from the date of communication of such amendments.

3. Any recommended amendment to the General Annex or the Specific Annexes or Chapters therein shall be deemed to have been accepted six months after the date the recommended amendment was communicated to Contracting Parties, unless:

A. there has been an objection by a Contracting Party or, in the case of a Specific Annex or Chapter, by a Contracting Party bound by that Specific Annex or Chapter; or

B. a Contracting Party informs the Secretary General of the Council that, although it intends to accept the recommended amendment, the conditions necessary for such acceptance are not yet fulfilled.

4. If a Contracting Party sends the Secretary General of the Council a communication as provided for in paragraph 3 (b) of this Article, it may, so long as it has not notified the Secretary General of the Council of its acceptance of the recommended amendment, submit an objection to that amendment within a period of eighteen months following the expiry of the six-month period referred to in paragraph 3 of this Article.

5. If an objection to the recommended amendment is notified in accordance with the terms of paragraph 3 (a) or 4 of this Article, the amendment shall be deemed not to have been accepted and shall be of no effect.

6. If any Contracting Party has sent a communication in accordance with paragraph 3 (b) of this Article, the amendment shall be deemed to have been accepted on the earlier of the following two dates:

A. the date by which all the Contracting Parties which sent such communications have notified the Secretary General of the Council of their acceptance of the recommended amendment, provided that, if all the acceptances were notified before the expiry of the period of six months referred to in paragraph 3 of this Article, that date shall be taken to be the date of expiry of the said six-month period;

B. the date of expiry of the eighteen-month period referred to in paragraph 4 of this Article.

7. Any amendment to the General Annex or the Specific Annexes or Chapters therein deemed to be accepted shall enter into force either six months after the date on which it was deemed to be accepted or, if a different period is specified in the recommended amendment, on the expiry of that period after the date on which the amendment was deemed to be accepted.

8. The Secretary General of the Council shall, as soon as possible, notify the Contracting Parties to this Convention of any objection to the recommended amendment made in accordance with paragraph 3 (a), and of any communication received in accordance with paragraph 3 (b), of this Article. The Secretary General of the Council shall subsequently inform the Contracting Parties whether the Contracting Party or Parties which have sent such a communication raise an objection to the recommended amendment or accept it.

Article 16

1. Notwithstanding the amendment procedure laid down in Article 15 of this Convention, the Management Committee in accordance with Article 6 may decide to amend any Recommended Practice or to incorporate new Recommended Practices to any Specific Annex or Chapter therein. Each Contracting Party shall be invited by the Secretary General of the Council to participate in the deliberations of the Management Committee. The text of any such amendment or new Recommended Practice so decided upon shall be communicated by the Secretary General of the Council to the Contracting Parties and those Members of the Council that are not Contracting Parties to this Convention.

2. Any amendment or incorporation of new Recommended Practices decided upon under paragraph 1 of this Article shall enter into force six months after their communication by the Secretary General of the Council. Each Contracting Party bound by a Specific Annex or Chapter therein forming the subject of such amendments or incorporation of new Recommended Practices shall be deemed to have accepted those amendments or new Recommended Practices unless it enters a reservation under the procedure of Article 12 of this Convention.

Article 17

Duration of accession

1. This Convention is of unlimited duration but any Contracting Party may denounce it at any time after the date of its entry into force under Article 18 thereof.

2. The denunciation shall be notified by an instrument in writing, deposited with the depositary.

3. The denunciation shall take effect six months after the receipt of the instrument of denunciation by the depositary.

4. The provisions of paragraphs 2 and 3 of this Article shall also apply in respect of the Specific Annexes or Chapters therein, for which any Contracting Party may withdraw its acceptance at any time after the date of the entry into force.

5. Any Contracting Party which withdraws its acceptance of the General Annex shall be deemed to have denounced the Convention. In this case, the provisions of paragraphs 2 and 3 also apply.

Chapter V - Final provisions

CHAPTER V

FINAL PROVISIONS

Article 18

Entry into force of the Convention

1. This Convention shall enter into force three months after five of the entities referred to in paragraphs 1 and 5 of Article 8 thereof have signed the Convention without reservation of ratification or have deposited their instruments of ratification or accession.

2. This Convention shall enter into force for any Contracting Party three months after it has become a Contracting Party in accordance with the provisions of Article 8.

3. Any Specific Annex or Chapter therein to this Convention shall enter into force three months after five Contracting Parties have accepted that Specific Annex or that Chapter.

4. After any Specific Annex or Chapter therein has entered into force in accordance with paragraph 3 of this Article, that Specific Annex or Chapter therein shall enter into force for any Contracting Party three months after it has notified its acceptance. No Specific Annex or Chapter therein shall, however, enter into force for a Contracting Party before this Convention has entered into force for that Contracting Party.

Article 19

Depositary of the Convention

1. This Convention, all signatures with or without reservation of ratification and all instruments of ratification or accession shall be deposited with the Secretary General of the Council.

2. The depositary shall:

A. receive and keep custody of the original texts of this Convention;

B. prepare certified copies of the original texts of this Convention and transmit them to the Contracting Parties and those Members of the Council that are not Contracting Parties and the Secretary General of the United Nations;

C. receive any signature with or without reservation of ratification, ratification or accession to this Convention and receive and keep custody of any instruments, notifications and communications relating to it;

D. examine whether the signature or any instrument, notification or communication relating to this Convention is in due and proper form and, if need be, bring the matter to the attention of the Contracting Party in question;

E. notify the Contracting Parties, those Members of the Council that are not Contracting Parties, and the Secretary General of the United Nations of:

- signatures, ratifications, accessions and acceptances of Annexes and Chapters under Article 8 of this Convention;

- new Chapters of the General Annex and new Specific Annexes or Chapters therein which the Management Committee decides to recommend to incorporate in this Convention;

- the date of entry into force of this Convention, of the General Annex and of each Specific Annex or Chapter therein in accordance with Article 18 of this Convention;

- notifications received in accordance with Articles 8, 10, 11,12 and 13 of this Convention; 14.

- withdrawals of acceptances of Annexes/Chapters by Contracting Parties;

- denunciations under Article 17 of this Convention; and

- any amendment accepted in accordance with Article 15 of this Convention and the date of its entry into force.

3. In the event of any difference appearing between a Contracting Party and the depositary as to the performance of the latter's functions, the depositary or that Contracting Party shall bring the question to the attention of the other Contracting Parties and the signatories or, as the case may be, the Management Committee or the Council.

Article 20

Registration and authentic texts

In accordance with Article 102 of the Charter of the United Nations, this Convention shall be registered with the Secretariat of the United Nations at the request of the Secretary General of the Council.

In witness whereof the undersigned, being duly authorized thereto, have signed this Convention.

Done at Kyoto, this eighteenth day of May nineteen hundred and seventy-three in the English and French languages, both texts being equally authentic, in a single original which shall be deposited with the Secretary General of the Council who shall transmit certified copies to all the entities referred to in paragraph 1 of Article 8 of this Convention.

General Annex

Chapter 1 - General Principles

CHAPTER 1

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Legal Text

1.1. Standard

The Definitions, Standards and Transitional Standards in this Annex shall apply to Customs procedures and practices specified in this Annex and, insofar as applicable, to procedures and practices in the Specific Annexes.

1.2. Standard

The conditions to be fulfilled and Customs formalities to be accomplished for procedures and practices in this Annex and in the Specific Annexes shall be specified in national legislation and shall be as simple as possible.

1.3. Standard

The Customs shall institute and maintain formal consultative relationships with the trade to increase co-operation and facilitate participation in establishing the most effective methods of working commensurate with national provisions and international agreements.

Guidelines to Chapter 1

Guidelines to the legal text

Chapter 1

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

|

There are Guidelines to all Chapters of the General Annex, except Chapter 2, “Definitions”, and for all the Chapters of the Specific Annexes in the revised Kyoto Convention. These Guidelines are not part of the legal text of the Convention and entail no legal obligations. They contain explanations of the provisions of the Convention and give examples of best practice or methods of application and future developments. They illustrate what Customs administrations can achieve and how various initiatives work. Customs administrations may adopt and implement those best practices that are most suited to their particular environment. If that practice is more liberal than required by a particular provision or procedure, such an application can be regarded as granting a greater facility in accordance with Article 2 of the Convention. |

1. Introduction

Customs Services play an integral role in world commerce. They have the essential task of enforcing the law, collecting duties and taxes, providing prompt clearance of goods and ensuring compliance. The manner in which Customs conducts its business has an impact on the movement of persons and goods in international trade. To reduce the Customs intervention in the international flow of goods to a minimum, modern Customs administrations must develop comprehensive and transparent Customs legislation.

The objective of this Convention is not only to meet the needs of the trading community to facilitate the movements of goods but also to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of compliance with Customs law and Customs control. Rapid changes in international trade, globalization and information technology make it necessary for Customs administrations to modify their procedures and practices to take account of these new developments.

There are several international conventions and other instruments designed to harmonize and simplify Customs procedures. This Convention, which contains the basic principles for all Customs procedures and practices, is one of them. The Recommendations of the UNCTAD Columbus Declaration give a broader view of Customs involvement in international trade. The International Customs Guidelines of the International Chamber of Commerce provide another model for an effective and efficient Customs administration. Other Conventions address specific means of transport or specific Customs procedures, such as the Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic, the Facilitation Annex (9) to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, the Istanbul Convention on the Temporary Admission and the TIR Convention on the International Transport of Goods.

This Convention provides the underlying conditions and instruments to help the Contracting Parties to achieve a modern Customs administration and to adapt their national legislation, without prejudice to effective control methods, to meet the requirements of a simpler, harmonized and more flexible approach. This will also allow international business to meet its Customs obligations as efficiently as possible.

2. Structure of the Convention

Standard 1.1

The Definitions, Standards and Transitional Standards in this Annex shall apply to Customs procedures and practices specified in this Annex and, insofar as applicable, to procedures and practices in the Specific Annexes.

The amended Kyoto Convention contains a General Annex and a number of Specific Annexes to make its structure more logical. The General Annex deals with the core principles for all procedures and practices to ensure that these are uniformly applied by Customs administrations. The Specific Annexes cover the individual Customs procedures and practices. The provisions of the General Annex also apply to the procedures and practices set out in the Specific Annexes. The Convention covers not only Customs procedures relating to import, export, transit, processing, etc., but also Customs practices concerning rules that are not necessarily applicable to goods but are required to regulate other matters such as Customs control, the application of information technology, appeals, offences or relations with the business community.

2.1. Acceptance of Annexes

The Body of the Convention and the General Annex are obligatory for accession to the Convention. A Contracting Party is free, however, to accept all the Specific Annexes or only a number of Specific Annexes or Chapters dependent upon their specific requirements. It is recommended that at least the Specific Annexes on home use and export are accepted, as well as those concerning the formalities prior to the lodgement of the Goods declaration and those for warehouses, transit and processing. Acceptance of these basic procedures which are implemented by most Customs administrations will provide the first level of simplification and harmonization of Customs procedures across different administrations.

2.2. Reservations

In order to achieve a greater level of harmonization of Customs legislation worldwide, no reservations are allowed to the definitions or other provisions of the General Annex or to the definitions and Standards in the Specific Annexes which a Contracting Party has accepted.

2.3. General Annex

The General Annex reflects the main Customs functions in its Definitions, Standards and Transitional Standards which all have the same legal value. The application of the Standards and Transitional Standards is considered necessary to achieve harmonization and simplification of the Customs procedure or practice concerned. The difference between a Standard and a Transitional Standard is the longer period for implementation for the Transitional Standard. A Standard has to be implemented within 36 months. A Transitional Standard on the other hand has 60 months for implementation. This transitional period is to facilitate Contracting Parties in their acceptance of or accession to this Convention and to provide for the time required to adapt their procedures and practices to the objectives of the Convention.

The General Annex applies to all the Customs procedures and practices as well as to those contained in the Specific Annexes and their Chapters. This method of application of the provisions of the General Annex ensures that all core provisions of a general nature are applied in all Customs procedures and practices without it being necessary to repeat them in all those individual procedures and practices. This also prevents conflicting provisions concerning core provisions in the different Annexes or Chapters of the Convention.

Thus all the definitions of terms necessary for the interpretation of more than one Annex to the Convention are contained in the General Annex. The definitions of terms applicable to only one Specific Annex or Chapter therein are contained only in that Specific Annex or Chapter.

2.4. Specific Annexes and Chapters

Each Specific Annex or Chapter deals with a particular Customs procedure or practice covering, for example, import, export, transit, warehousing and processing, or a Customs practice, such as origin, Customs offences, treatment of travellers and postal formalities.

In a Specific Annex only those provisions that are applicable to the particular Customs procedure or practice are incorporated.

2.5. Guidelines

There are Guidelines to all the Chapters of the General Annex, except Chapter 2, “Definitions”, and for all the Specific Annexes and their Chapters. The Guidelines are not part of the legal text of the Convention and entail no legal obligations. They contain explanations of the provisions of the Convention and give examples of best practice or methods of application and future developments. They also reflect measures adopted by the WCO to secure and facilitate the international supply chain. They illustrate what Customs administrations can achieve, and how various initiatives can work. Customs administrations may adopt and implement those best practices that are most suited to their particular environment. If that best practice is more liberal than required by a particular provision or procedure, such an application can be regarded as granting a greater facility in accordance with Article 2 of the Convention.

3. Implementation of the provisions

Standard 1.2

The conditions to be fulfilled and Customs formalities to be accomplished for procedures and practices in this Annex and in the Specific Annexes shall be specified in national legislation and shall be as simple as possible.

Contracting Parties have to bring the Standards and Recommended Practices which they have accepted into force nationally. Their national legislation must therefore include at least the basic rules from the General Annex, together with detailed regulations for their implementation. These regulations will not necessarily be confined to Customs legislation and may apply to such instruments as official notifications, charters or ministerial decrees according to each Contracting Party's administrative system.

For the purpose of this Convention the concept of “national legislation” includes domestic legislation in situations where national legislation is not appropriate or applicable.

The basic rules covered in national legislation must include the conditions under which a Customs procedure is to be accomplished. In order to secure maximum compliance from national and international businesses, Customs administrations must ensure that their legislation and regulations are transparent, predictable, consistent and reliable. Information must therefore be provided to all parties involved in Customs transactions and must be easily accessible.

In addition to legislative measures for implementation of the provisions of this Convention, Contracting Parties must also provide for facilities, personnel and equipment to give actual effect to the objectives of the Convention. Such support is indispensable especially in light of new developments in the use of information technology, risk-management and audit-based controls.

4. Co-operation with the Trade

Standard 1.3

The Customs shall institute and maintain formal consultative relationships with the trade to increase co-operation and facilitate participation in establishing the most effective methods of working commensurate with national provisions and international agreements.

To address the rapidly growing volume of international trade, active co-operation and intensive communication between Customs and the trade are essential to complement each other’s objectives and responsibilities. Since Customs are an important element in international trade procedures, it is important that Customs administrations make use of modern working methods to administer their operations and that they strive to facilitate trade to the maximum extent possible.

In an ever-changing trading environment, where speed means a trader’s livelihood, Customs and the trade have to develop modern methods together. To achieve this a consultative relationship is indispensable and the use of modern information technology essential for the efficient and fast exchange of information. Before Customs implement changes or introduces new procedures or automated systems, Customs should consult with appropriate representatives of the trade so that both can gear their activities in consideration of each other’s needs. In this connection, reference is made to the Customs-Business partnership arrangements outlined in the SAFE Framework of Standards to Secure and Facilitate Global Trade.

In order to develop instruments for co-operation and consultation, Customs has to establish formal consultative relationships with the different national trade associations. Co-operation between Customs and the trade can result in formal Memoranda of Understanding which serve to benefit the accomplishment of both parties’ objectives and responsibilities. Further information on such Memoranda of Understanding can be found in the Guidelines to Chapter 6 of the General Annex on Customs control.

Chapter 2 - Definitions

CHAPTER 2

DEFINITIONS

Legal Text

For the purposes of the Annexes to this Convention:

E1./ F23.

“appeal ” means the act by which a person who is directly affected by a decision or omission of the Customs and who considers himself to be aggrieved thereby seeks redress before a competent authority;

E2./ F19.

“assessment of duties and taxes ” means the determination of the amount of duties and taxes payable;

E3./ F4.

“audit-based control ” means measures by which the Customs satisfy themselves as to the accuracy and authenticity of declarations through the examination of the relevant books, records, business systems and commercial data held by persons concerned;

E4./ F15.

“checking the Goods declaration ” means the action taken by the Customs to satisfy themselves that the Goods declaration is correctly made out and that the supporting documents required fulfil the prescribed conditions;

E5./ F9.

“clearance ” means the accomplishment of the Customs formalities necessary to allow goods to enter home use, to be exported or to be placed under another Customs procedure;

E6./ F10.

“Customs ” means the Government Service which is responsible for the administration of Customs law and the collection of duties and taxes and which also has the responsibility for the application of other laws and regulations relating to the importation, exportation, movement or storage of goods;

E7./ F3.

“Customs control ” means measures applied by the Customs to ensure compliance with Customs law;

E8./ F11.

“Customs duties ” means the duties laid down in the Customs tariff to which goods are liable on entering or leaving the Customs territory;

E9./ F16.

“Customs formalities ” means all the operations which must be carried out by the persons concerned and by the Customs in order to comply with the Customs law;

E10./ F18.

“Customs law ” means the statutory and regulatory provisions relating to the importation, exportation, movement or storage of goods, the administration and enforcement of which are specifically charged to the Customs, and any regulations made by the Customs under their statutory powers;

E11./ F2.

“Customs office ” means the Customs administrative unit competent for the performance of Customs formalities, and the premises or other areas approved for that purpose by the competent authorities;

E12./ F25.

“Customs territory ” means the territory in which the Customs law of a Contracting Party applies;

E13./ F6.

“decision ” means the individual act by which the Customs decide upon a matter relating to Customs law;

E14./ F7.

“declarant ” means any person who makes a Goods declaration or in whose name such a declaration is made;

E15./ F5.

“due date ” means the date when payment of duties and taxes is due;

E16./ F12.

“duties and taxes ” means import duties and taxes and/or export duties and taxes;

E17./ F27.

“examination of goods ” means the physical inspection of goods by the Customs to satisfy themselves that the nature, origin, condition, quantity and value of the goods are in accordance with the particulars furnished in the Goods declaration;

E18./ F13.

“export duties and taxes ” means Customs duties and all other duties, taxes or charges which are collected on or in connection with the exportation of goods, but not including any charges which are limited in amount to the approximate cost of services rendered or collected by the Customs on behalf of another national authority;

E19./ F8.

“Goods declaration ” means a statement made in the manner prescribed by the Customs, by which the persons concerned indicate the Customs procedure to be applied to the goods and furnish the particulars which the Customs require for its application;

E20./ F14.

“import duties and taxes ” means Customs duties and all other duties, taxes or charges which are collected on or in connection with the importation of goods, but not including any charges which are limited in amount to the approximate cost of services rendered or collected by the Customs on behalf of another national authority;

E21./ F1.

“mutual administrative assistance ” means actions of a Customs administration on behalf of or in collaboration with another Customs administration for the proper application of Customs law and for the prevention, investigation and repression of Customs offences;

E22./ F21.

“omission ” means the failure to act or give a decision required of the Customs by Customs law within a reasonable time on a matter duly submitted to them;

E23./ F22.

“person ” means both natural and legal persons, unless the context otherwise requires;

E24./ F20.

“release of goods ” means the action by the Customs to permit goods undergoing clearance to be placed at the disposal of the persons concerned;

E25./ F24.

“repayment ” means the refund, in whole or in part, of duties and taxes paid on goods and the remission, in whole or in part, of duties and taxes where payment has not been made;

E26./ F17.

“security ” means that which ensures to the satisfaction of the Customs that an obligation to the Customs will be fulfilled. Security is described as “general” when it ensures that the obligations arising from several operations will be fulfilled;

E27./ F26.

“third party ” means any person who deals directly with the Customs, for and on behalf of another person, relating to the importation, exportation, movement or storage of goods.

Guidelines to Chapter 2

Guidelines to the legal text

Chapter 2

DEFINITIONS

For the purposes of the Annexes to this Convention :

|

E1./ F23. |

“appeal” means the act by which a person who is directly affected by a decision or omission of the Customs and who considers himself to be aggrieved thereby seeks redress before a competent authority; |

|

E2./ F19. |

“assessment of duties and taxes” means the determination of the amount of duties and taxes payable; |

|

E3./ F4. |

“audit-based control” means measures by which the Customs satisfy themselves as to the accuracy and authenticity of declarations through the examination of the relevant books, records, business systems and commercial data held by persons concerned; |

|

E4./ F15. |

“checking the Goods declaration” means the action taken by the Customs to satisfy themselves that the Goods declaration is correctly made out and that the supporting documents required fulfil the prescribed conditions; |

|

E5./ F9. |

“clearance” means the accomplishment of the Customs formalities necessary to allow goods to enter home use, to be exported or to be placed under another Customs procedure; |

|

E6./ F10. |

“Customs” means the Government Service which is responsible for the administration of Customs law and the collection of duties and taxes and which also has the responsibility for the application of other laws and regulations relating to the importation, exportation, movement or storage of goods; |

|

E7./ F3. |

“Customs control” means measures applied by the Customs to ensure compliance with Customs law; |

|

E8./ F11. |

“Customs duties” means the duties laid down in the Customs tariff to which goods are liable on entering or leaving the Customs territory; |

|

E9./ F16. |

“Customs formalities” means all the operations which must be carried out by the persons concerned and by the Customs in order to comply with the Customs law; |

|

E10./ F18. |

“Customs law” means the statutory and regulatory provisions relating to the importation, exportation, movement or storage of goods, the administration and enforcement of which are specifically charged to the Customs, and any regulations made by the Customs under their statutory powers; |

|

E11./ F2. |

“Customs office” means the Customs administrative unit competent for the performance of Customs formalities, and the premises or other areas approved for that purpose by the competent authorities; |

|

E12./ F25. |

“Customs territory” means the territory in which the Customs law of a Contracting Party applies; |

|

E13./ F6. |

“decision” means the individual act by which the Customs decide upon a matter relating to Customs law; |

|

E14./ F7. |

“declarant” means any person who makes a Goods declaration or in whose name such a declaration is made; |

|

E15./ F5. |

“due date” means the date when payment of duties and taxes is due; |

|

E16./ F12. |

“duties and taxes” means import duties and taxes and/or export duties and taxes; |

|

E17./ F27. |

“examination of goods” means the physical inspection of goods by the Customs to satisfy themselves that the nature, origin, condition, quantity and value of the goods are in accordance with the particulars furnished in the Goods declaration; |

|

E18./ F13. |

“export duties and taxes” means Customs duties and all other duties, taxes or charges which are collected on or in connection with the exportation of goods, but not including any charges which are limited in amount to the approximate cost of services rendered or collected by the Customs on behalf of another national authority; |

|

E19./ F8. |

“Goods declaration” means a statement made in the manner prescribed by the Customs, by which the persons concerned indicate the Customs procedure to be applied to the goods and furnish the particulars which the Customs require for its application; |

|

E20./ F14. |

“import duties and taxes” means Customs duties and all other duties, taxes or charges which are collected on or in connection with the importation of goods, but not including any charges which are limited in amount to the approximate cost of services rendered or collected by the Customs on behalf of another national authority; |

|

E21./ F1. |

“mutual administrative assistance” means actions of a Customs administration on behalf of or in collaboration with another Customs administration for the proper application of Customs law and for the prevention, investigation and repression of Customs offences; |

|

E22./ F21. |

“omission” means the failure to act or give a decision required of the Customs by Customs law within a reasonable time on a matter duly submitted to them; |

|

E23./ F22. |

“person” means both natural and legal persons, unless the context otherwise requires; |

|

E24./ F20. |

“release of goods” means the action by the Customs to permit goods undergoing clearance to be placed at the disposal of the persons concerned; |

|

E25./ F24. |

“repayment” means the refund, in whole or in part, of duties and taxes paid on goods and the remission, in whole or in part, of duties and taxes where payment has not been made; |

|

E26./ F17. |

“security” means that which ensures to the satisfaction of the Customs that an obligation to the Customs will be fulfilled. Security is described as “general” when it ensures that the obligations arising from several operations will be fulfilled; |

|

E27./ F26. |

“third party” means any person who deals directly with the Customs, for and on behalf of another person, relating to the importation, exportation, movement or storage of goods. |

Chapter 3 - Clearance and other customs formalities

CHAPTER 3

CLEARANCE AND OTHER CUSTOMS FORMALITIES

Legal Text

Competent Customs offices

3.1. Standard

The Customs shall designate the Customs offices at which goods may be produced or cleared. In determining the competence and location of these offices and their hours of business, the factors to be taken into account shall include in particular the requirements of the trade.

3.2. Standard

At the request of the person concerned and for reasons deemed valid by the Customs, the latter shall, subject to the availability of resources, perform the functions laid down for the purposes of a Customs procedure and practice outside the designated hours of business or away from Customs offices. Any expenses chargeable by the Customs shall be limited to the approximate cost of the services rendered.

3.3. Standard

Where Customs offices are located at a common border crossing, the Customs administrations concerned shall correlate the business hours and the competence of those offices.

3.4. Transitional Standard

At common border crossings, the Customs administrations concerned shall, whenever possible, operate joint controls.

3.5. Transitional Standard

Where the Customs intend to establish a new Customs office or to convert an existing one at a common border crossing, they shall, wherever possible, co-operate with the neighbouring Customs to establish a juxtaposed Customs office to facilitate joint controls.

The Declarant

(a) Persons entitled to act as declarant

3.6. Standard

National legislation shall specify the conditions under which a person is entitled to act as declarant.

3.7. Standard

Any person having the right to dispose of the goods shall be entitled to act as declarant.

(b) Responsibilities of the declarant

3.8. Standard

The declarant shall be held responsible to the Customs for the accuracy of the particulars given in the Goods declaration and the payment of the duties and taxes.

(c) Rights of the declarant

3.9. Standard

Before lodging the Goods declaration the declarant shall be allowed, under such conditions as may be laid down by the Customs:

a. to inspect the goods; and

b. to draw samples.

3.10. Standard

The Customs shall not require a separate Goods declaration in respect of samples allowed to be drawn under Customs supervision, provided that such samples are included in the Goods declaration concerning the relevant consignment.

The Goods declaration

(a) Goods declaration format and contents

3.11. Standard

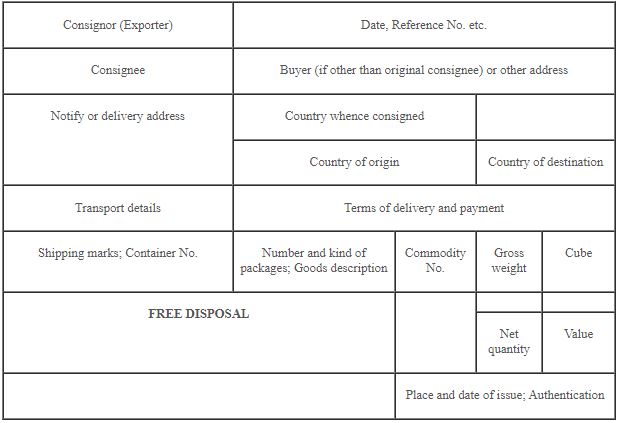

The contents of the Goods declaration shall be prescribed by the Customs. The paper format of the Goods declaration shall conform to the UN-layout key.

For automated Customs clearance processes, the format of the electronically lodged Goods declaration shall be based on international standards for electronic information exchange as prescribed in the Customs Co-operation Council Recommendations on information technology.

3.12. Standard

The Customs shall limit the data required in the Goods declaration to only such particulars as are deemed necessary for the assessment and collection of duties and taxes, the compilation of statistics and the application of Customs law.

3.13. Standard

Where, for reasons deemed valid by the Customs, the declarant does not have all the information required to make the Goods declaration, a provisional or incomplete Goods declaration shall be allowed to be lodged, provided that it contains the particulars deemed necessary by the Customs and that the declarant undertakes to complete it within a specified period.

3.14. Standard

If the Customs register a provisional or incomplete Goods declaration, the tariff treatment to be accorded to the goods shall not be different from that which would have been accorded had a complete and correct Goods declaration been lodged in the first instance.

The release of the goods shall not be delayed provided that any security required has been furnished to ensure collection of any applicable duties and taxes.

3.15. Standard

The Customs shall require the lodgement of the original Goods declaration and only the minimum number of copies necessary.

(b) Documents supporting the Goods declaration

3.16. Standard

In support of the Goods declaration the Customs shall require only those documents necessary to permit control of the operation and to ensure that all requirements relating to the application of Customs law have been complied with.

3.17. Standard

Where certain supporting documents cannot be lodged with the Goods declaration for reasons deemed valid by the Customs, they shall allow production of those documents within a specified period.

3.18. Transitional Standard

The Customs shall permit the lodgement of supporting documents by electronic means.

3.19. Standard

The Customs shall not require a translation of the particulars of supporting documents except when necessary to permit processing of the Goods declaration. Lodgement, registration and checking of the Goods declaration

3.20. Standard

The Customs shall permit the lodging of the Goods declaration at any designated Customs office.

3.21. Transitional Standard

The Customs shall permit the lodging of the Goods declaration by electronic means.

3.22. Standard

The Goods declaration shall be lodged during the hours designated by the Customs.

3.23. Standard

Where national legislation lays down a time limit for lodging the Goods declaration, the time allowed shall be sufficient to enable the declarant to complete the Goods declaration and to obtain the supporting documents required.

3.24. Standard

At the request of the declarant and for reasons deemed valid by the Customs, the latter shall extend the time limit prescribed for lodging the Goods declaration.

3.25. Standard

National legislation shall make provision for the lodging and registering or checking of the Goods declaration and supporting documents prior to the arrival of the goods.

3.26. Standard

When the Customs cannot register the Goods declaration, they shall state the reasons to the declarant.

3.27. Standard

The Customs shall permit the declarant to amend the Goods declaration that has already been lodged, provided that when the request is received they have not begun to check the Goods declaration or to examine the goods.

3.28. Transitional Standard

The Customs shall permit the declarant to amend the Goods declaration if a request is received after checking of the Goods declaration has commenced, if the reasons given by the declarant are deemed valid by the Customs.

3.29. Transitional Standard

The declarant shall be allowed to withdraw the Goods declaration and apply for another Customs procedure, provided that the request to do so is made to the Customs before the goods have been released and that the reasons are deemed valid by the Customs.

3.30. Standard

Checking the Goods declaration shall be effected at the same time or as soon as possible after the Goods declaration is registered.

3.31. Standard

For the purpose of checking the Goods declaration, the Customs shall take only such action as they deem essential to ensure compliance with Customs law.

Special Procedures for Authorized persons

3.32. Transitional Standard

For authorized persons who meet criteria specified by the Customs, including having an appropriate record of compliance with Customs requirements and a satisfactory system for managing their commercial records, the Customs shall provide for:

- release of the goods on the provision of the minimum information necessary to identify the goods and permit the subsequent completion of the final Goods declaration;

- clearance of the goods at the declarant's premises or another place authorized by the Customs; and, in addition, to the extent possible, other special procedures such as:

- allowing a single Goods declaration for all imports or exports in a given period where goods are imported or exported frequently by the same person;

- use of the authorized persons’ commercial records to self-assess their duty and tax liability and, where appropriate, to ensure compliance with other Customs requirements;

- allowing the lodgement of the Goods declaration by means of an entry in the records of the authorized person to be supported subsequently by a supplementary Goods declaration.

Examination of Goods

(a) Time required for examination of goods

3.33. Standard

When the Customs decide that goods declared shall be examined, this examination shall take place as soon as possible after the Goods declaration has been registered.

3.34. Standard

When scheduling examinations, priority shall be given to the examination of live animals and perishable goods and to other goods which the Customs accept are urgently required.

3.35. Transitional Standard

If the goods must be inspected by other competent authorities and the Customs also schedules an examination, the Customs shall ensure that the inspections are co-ordinated and, if possible, carried out at the same time.

(b) Presence of the declarant at examination of goods

3.36. Standard

The Customs shall consider requests by the declarant to be present or to be represented at the examination of the goods. Such requests shall be granted unless exceptional circumstances exist.

3.37. Standard

If the Customs deem it useful, they shall require the declarant to be present or to be represented at the examination of the goods to give them any assistance necessary to facilitate the examination.

(c) Sampling by the Customs

3.38. Standard

Samples shall be taken only where deemed necessary by the Customs to establish the tariff description and/or value of goods declared or to ensure the application of other provisions of national legislation. Samples drawn shall be as small as possible.

Errors

3.39. Standard

The Customs shall not impose substantial penalties for errors where they are satisfied that such errors are inadvertent and that there has been no fraudulent intent or gross negligence. Where they consider it necessary to discourage a repetition of such errors, a penalty may be imposed but shall be no greater than is necessary for this purpose.

Release of Goods

3.40. Standard

Goods declared shall be released as soon as the Customs have examined them or decided not to examine them, provided that :

- no offence has been found;

- the import or export licence or any other documents required have been acquired;

- all permits relating to the procedure concerned have been acquired; and

- any duties and taxes have been paid or that appropriate action has been taken to ensure their collection.

3.41. Standard

If the Customs are satisfied that the declarant will subsequently accomplish all the formalities in respect of clearance they shall release the goods, provided that the declarant produces a commercial or official document giving the main particulars of the consignment concerned and acceptable to the Customs, and that security, where required, has been furnished to ensure collection of any applicable duties and taxes.

3.42. Standard

When the Customs decide that they require laboratory analysis of samples, detailed technical documents or expert advice, they shall release the goods before the results of such examination are known, provided that any security required has been furnished and provided they are satisfied that the goods are not subject to prohibitions or restrictions.

3.43. Standard

When an offence has been detected, the Customs shall not wait for the completion of administrative or legal action before they release the goods, provided that the goods are not liable to confiscation or forfeiture or to be needed as evidence at some later stage and that the declarant pays the duties and taxes and furnishes security to ensure collection of any additional duties and taxes and of any penalties which may be imposed.

Abandonment or destruction of goods

3.44. Standard

When goods have not yet been released for home use or when they have been placed under another Customs procedure, and provided that no offence has been detected, the person concerned shall not be required to pay the duties and taxes or shall be entitled to repayment thereof:

- when, at his request, such goods are abandoned to the Revenue or destroyed or rendered commercially valueless under Customs control, as the Customs may decide. Any costs involved shall be borne by the person concerned;

- when such goods are destroyed or irrecoverably lost by accident or force majeure, provided that such destruction or loss is duly established to the satisfaction of the Customs;

- on shortages due to the nature of the goods when such shortages are duly established to the satisfaction of the Customs.

Any waste or scrap remaining after destruction shall be liable, if taken into home use or exported, to the duties and taxes that would be applicable to such waste or scrap imported or exported in that state.

3.45. Transitional Standard

When the Customs sell goods which have not been declared within the time allowed or could not be released although no offence has been discovered, the proceeds of the sale, after deduction of any duties and taxes and all other charges and expenses incurred, shall be made over to those persons entitled to receive them or, when this is not possible, held at their disposal for a specified period.

Guidelines to Chapter 3

Guidelines to the legal text

Chapter 3

CLEARANCE OTHER CUSTOMS FORMALITIES

Introduction

Clearance of goods and other Customs formalities form the core functions of Customs business. These functions place Customs administrations in the centre of world commerce since the manner in which they clear goods and carry out other related tasks, such as enforcing the law and collecting duties and taxes, has a great impact on national and international economy.

There are various Customs formalities to be accomplished when goods are brought into a Customs territory in order to ensure compliance with Customs law. These are the operations that must be carried out by both the persons concerned with the goods and by Customs in order to comply with the statutory or regulatory provisions which Customs has responsibility to enforce. Examples of Customs formalities are the specific actions that must be taken to clear goods for home use, exportation, temporary admission, warehousing or Customs transit. In addition, there are other Customs formalities that must be complied with from the time the goods are introduced into a Customs territory, regardless of the mode of transport that carried the goods, until they are placed under a specific Customs procedure.

The Customs formalities place obligations on the person concerned with the goods. This person is generally the owner of the goods, a third party designated by the owner or a transporter of the goods, depending on the formality to be completed. The overall obligations are to produce the goods and the means of transport to Customs at the earliest possible time; to lodge the Goods declaration with any required supporting documents (invoice, import license, certificate of origin, etc.); to furnish security where appropriate and to pay duties and taxes when applicable. There are also obligations on Customs which include establishing Customs offices, designating the hours of business, checking the Goods declaration, examining the goods, assessing and collecting duties and taxes, and releasing the goods.

These formalities are essential to ensure compliance with Customs laws and regulations and to ensure that Customs’ revenue and regulatory interests are safeguarded. At the same time they should be as simple as possible and should cause a minimum of inconvenience to international trade.

The formalities concerning assessment, collection and payment of duties and taxes are covered in Chapter 4 of the General Annex and the corresponding Guidelines, whereas matters concerning security are dealt with in Chapter 5 of the General Annex and the corresponding Guidelines.

In keeping with the principles of transparency and a system of open government, which includes the Customs administration, all information pertaining to Customs formalities must be made available in accordance with the principles laid down in Chapter 9 of the General Annex.

There are eleven parts to these Guidelines for Chapter 3. They deal with the following topics :

Part 1 Establishment of Customs offices

Part 2 Rights and responsibilities of the declarant

Part 3 The Goods declaration

Part 4 Lodgement and registration of the Goods declaration

Part 5 Amendment or withdrawal of the Goods declaration

Part 6 Checking the Goods declaration

Part 7 Special procedures for authorized persons

Part 8 Examination and sampling of the goods

Part 9 Errors

Part 10 Release of the goods

Part 11 Abandonment or destruction of goods

These Guidelines must be read in conjunction with the legal text contained in Chapter 3 of the General Annex.

It is important to reiterate that all the provisions in the General Annex apply to the provisions of the Specific Annexes. This is the reason that Standard 1 in each Chapter of each Specific Annex states that the procedure or practice is covered by the provisions of that Chapter and, insofar as applicable, by the provisions of the General Annex. Thus, every procedure or practice must be read in conjunction with the provisions of this Chapter of the General Annex in particular.

This Chapter, however, does not cover procedures relating to travellers and postal traffic. These subjects are covered in Chapters 1 and 2 of Specific Annex J, Special procedures. For these procedures the clearance formalities may be slightly different from those specified in the General Annex.

1. Part 1 – Establishment of Customs offices

1.1. Competent Customs offices

Formalities for clearing goods generally have to be completed at a Customs office. Customs administrations will not only establish Customs offices at their borders, but also at appropriate locations inland. The need to establish a Customs office will be based on the volumes of traffic, goods and travellers that enter the Customs territory at land routes, ports, airports and inland locations.

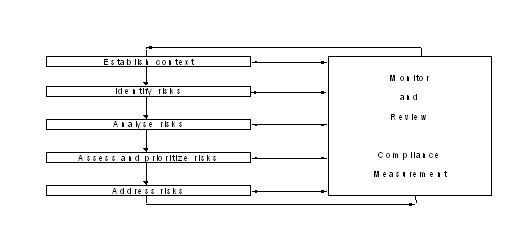

Where these volumes are sufficient to justify the establishment of a Customs office, Customs and other regulatory authorities involved in clearing goods, travellers and conveyances must proceed in co-operation with the trading community.